Positive Reinforcement

Schulze also draws to our attention the terminology employed for reinforcement. Terms such as “brilliant” and “excellent” are good, but if they are overly used they will become redundant. It’s hard for me to say now, how much praise I give. I see myself as a strict teacher – no playing until what we need to be done is done! However, I do give rewards, almost always preferring to hand those out at the end of class.

Positive Reinforcement: Real-life Example

Actually, I do recall now, with my young ones recently, that before I sent them out, I told them (in Chinese – but I usually NEVER speak Chinese with them) something like, “Today, you students worked well. Very well,” and handed out some point cards (which they are able to collect and exchange for small prizes such as stationary). There were smiles all round, so I think everyone was happy in that moment. And it was powerful because I rarely praise them in such a direct fashion. Thinking about the cards we give, I’m not a huge fan because they can be seen as bribery, which we know is not beneficial to learning. “If reinforcement is seen as a means of control for the benefit of the controller, then it is less likely to be effective” (Leiberman, 1990, p275).

Negative Reinforcement

In Shulze’s article, there is some confusion over punishment, or negative reinforcement: “When punishment is immediate, firm, accompanied by a clear (and fair) explanation, and when it occurs in a variety of settings, it can be a powerful tool for eliminating undesirable behaviour” (Leiberman, 1990, p243). However, at the same time, punishment has bad side affects, such as fear and anxiety, which may inhibit attention.

My Reflections

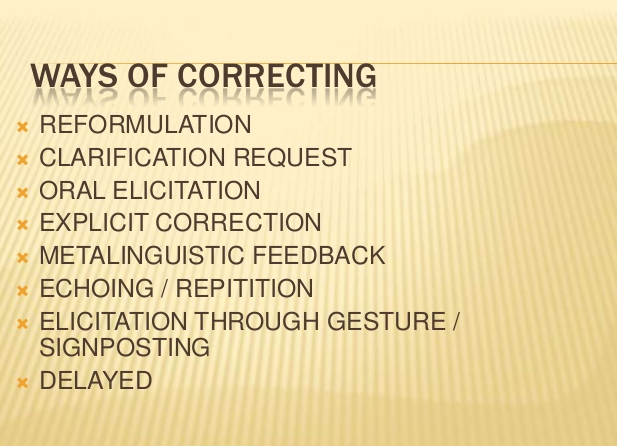

I do feel that my handling of feedback may lead to fossilisation (I often say that I can understood almost anything anyone says in English, no matter their level, because I want to understand, even if the utterances are not grammatically, or pragmatically, correct), when instead I should be employing negative feedback which would allow learners to work on their error. (“here, positive cognitive feedback means that the recipient of a message signals that he or she understood the message independent of the number of errors. Negative feedback refers to a reply which says that the utterance has not been understood.”)

Effective feedback relates to the nature of the feedback signals (Ellis, 1994). According to Ellis’ findings, learners tend to rephrase their utterances after clarification requests but were less likely to rephrase after confirmation requests or repetitions. On the internet I found some useful advice that explains that clarifying involves non-judgemental questioning and summarising and seeking feedback as to its accuracy.

Admit if you are unsure about what the speaker means.

Ask for repetition.

State what the speaker has said as you understand it, and check whether this is what they really said.

Ask for specific examples.

Use open, non-directive questions – if appropriate

Ask if you have got it right and be prepared to be corrected

Some examples of non-directive clarification-seeking questions are:

“I’m not quite sure I understand what you are saying”

“I don’t feel clear about the main issue here.”

“When you said …….. what did you mean?”

“Could you repeat …?”

Similarly, this document entitled Interaction and Negotiation of Meaning explains the differences between clarification requests, confirmation checks and comprehension checks and provides a transcript with examples.

Sources

Cook, Vivian J. “Chomsky’s universal grammar and second language learning.”Applied Linguistics 6.1 (1985): 2-18. Universal Grammar Theory and the Classroom Experience

Schulze, Mathias. “Grammatical errors and feedback: some theoretical insights.” CALICO Journal 20.3 (2003): 437-450.