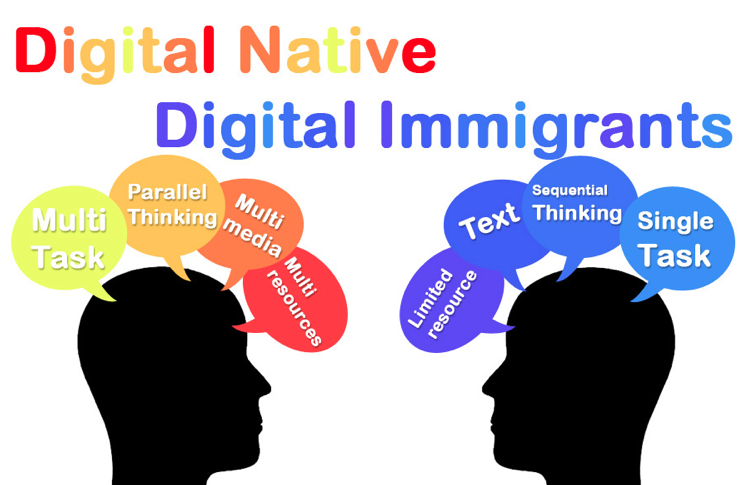

In his work Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants, Prensky (2001) claims that our students think and learn differently from their teachers because, while the former are digital language native speakers, the latter have, at best, learnt their digital language as a foreign language. Thus, while our students have native speaker intuition, teachers do not.

My reaction to Prensky’s language learning/acquisition analogy

I am concerned about the socio-economic implications of being a Digital Native or Digital Immigrant. Attending a school with technological resources or having personal access to digital technology is, in large part, related to where and to whom you were born. In the Chinese context, most schools are still characterised as having large class sizes, and are heavily dependent on the blackboard. So here, it is less about an active resistance to Prensky’s idea of digital “singularity” (Prensky, 2001:1), and more about simple economics, that maintains the “Immigrant/Native divide” (Prensky, 2001:3). At the same time, I must admit that, despite budget restrictions at local authority level in China, the incessant popularity of digital gadgets, means that even the children of those on low incomes are coming to school with iPhones and iPads in hand. Indeed, some Chinese youngsters are going to extreme lengths to stay “on trend”.

Another issue I have with the adoption of the terms ‘native’ and ‘immigrant’, is the idea that you are very much one or the other. I find such labels limiting, disliking the notion that there is no in-between, nor easy way to attain a higher status. I would place myself in the middle of this spectrum and concur that “the debate must no longer be about whether to use calculators and computers…but rather how to use them…” (Prensky, 2001:5) Key words such as “invent”, “adapting”, “mind-shift” and “re-thinking”, pepper Prensky’s publication, emphasising the responsibility of educators to re-imagine how and what to teach.

While I agree with Prensky’s assertion that students today are “native speakers” of the language that is digital technology, it is not to say they are effective communicators. Similarly, neither is it true to assume that if a teacher uses a technology, then they are able to employ them effectively in the classroom. After all, “…technology only provides a set of tools that are, for the most part, methodologically neutral” (Blake, 2008: 2). It’s what you do with them that counts.

But how to move forward with all of this technological ‘change’ and differing levels of computer competence? If these skills don’t come natural to digital “in-betweeners” such as myself, then, as Prensky suggests, “we do need to figure it out” (Prensky, 2001:4) Circling back to the idea that budgets are crucial for professional and technological advancement in schools today, however, I do think that no matter the enthusiasm of Digital Immigrant educators for their own training and education, “their successes will come that much sooner if their administrations support them” (Prensky, 2001:6). As someone who has initiated and paid for all of her trainings to date, I can confirm that administrative support would be warmly welcome.

References

Blake, R.J, (2008) Brave New Digital Classroom: Technology and Foreign Language Learning. 1st ed. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press

Prensky, Marc (2001) ‘Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants’, On the Horizon 9, 5, MCB University Press